“I have no choice,” he said again. “It’s like a dynasty. If the son doesn’t take the father’s place, the dynasty falls apart.”

Chaim Potok, ‘The Chosen’.

Following Damian’s eventual passing, his formerly disinterested wife saw fit to subsume his role as Evertonian El Patrón into her matriarchal manifesto. Previous interests such as music, film, and furiously moaning about a sudden proliferation of ‘fake scousers’ on TV were swiftly pushed to one side, and football became her primary focus.

However, anathema to her brood, she laid tentative claim to being a breed of fan who, while favouring the blues, fervently longed to see both sides of the city perform well. Pitiful attempts to get her partisan grandson to understand that, just like her precious John Lennon, all she was saying was ‘give peace a chance’ were promptly met with a firm “oh no” and banned (and if the term ‘plastic’ had been part of football parlance back then he’d have probably thrown that in too).

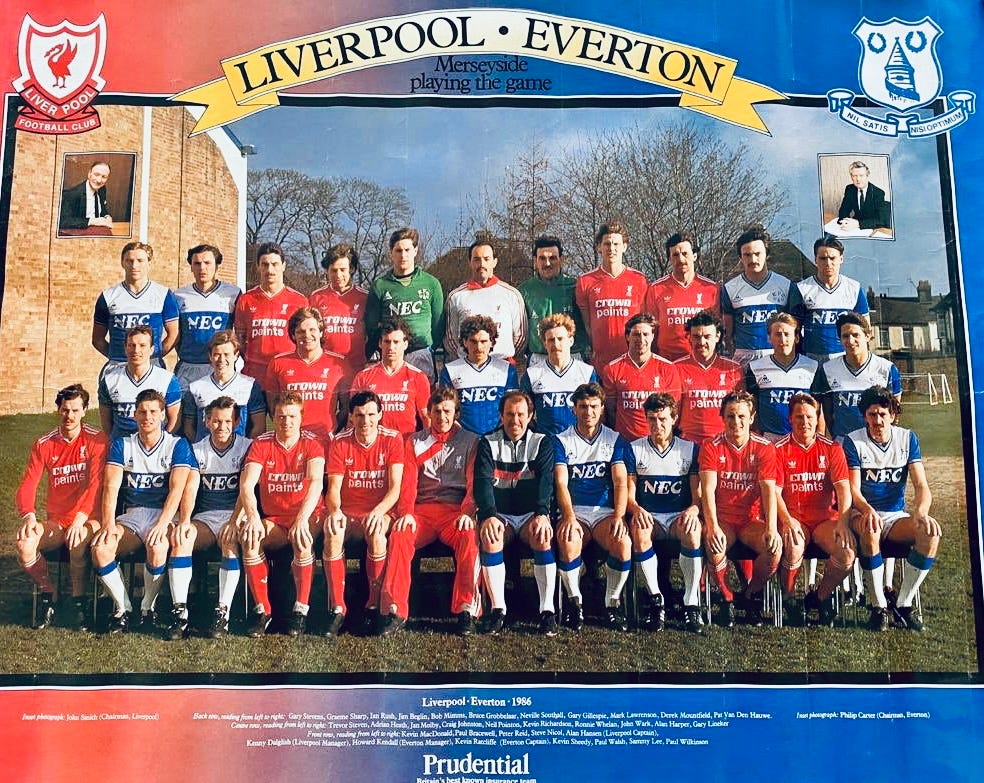

Prior to the first all-Merseyside FA Cup final, she bought him a big poster with the Everton and Liverpool squads posed together (seemingly all super pally in their scrote-pinching shorts) and made him slap it up on his bedroom wall straightaway.

Every night he went to sleep with the dead shark eyes of Rush, Dalglish, and Molby watching over him as his mind flitted through fantastically strange dreams featuring Megatron, Howling Mad Murdoch, and the hot blonde out of Buck Rogers minus her space bra. Whenever he woke up — usually at the point he had just pulled down his pants only for that sarcastic tin can Twiki to pipe up with “Biddy Biddy Biddy”— their judgmental red gaze was the first thing his groggy, guilt-ridden eyes were forced to readjust to.

“We’ll see who's too ashamed to look who in the eye after cup final day, you c##ts,” was both his coping method and constant mantra during those early May mornings. Complete and utter bluster, of course. His unblemished, yet to be downtrodden by the blue blight young mind just hadn’t experienced the getting your backside kicked reality of true Evertonianism by that point.

He would soon learn, though.

Boy, would he learn.

One of the few times he ever received a proper bollocking from his gran was when she happened to stop on her way to the bathroom and peered through his bedroom door before spying THAT poster and bellowing incredulously, “WHO’S DRAWN A BLOODY BELLEND ON BRUCE GROBELLAAR?”.

The fact that she had bought him the poster as a gift seemed to outweigh the fact that her grandson was technically correct with his cock graffiti. They were all pricks; there was no denying that, but it was the sheer principle of defacing a birthday present that irked her, so she scolded the “disrespectful little bugger” within an inch of his damn life anyway.

His cobbled-together defence that he would have simply made do with scrawling scruffy tashes on the insufferable twats if half the squad weren’t proudly sporting them already — as was the style at the time (© Grampa Simpson) — didn't quite cut it when it came to avoiding a severe arse tanning.

One bum cheek still bed sheet white, the other bruised a not-even-bordering-on-bloody-royal shade of blue, he was forced to squirm through the eventual, embarrassing, all-Merseyside encounter sat on a throbbing rear/fleshy replica of the horrific 85/86 Hafnia ‘bib’ his Everton heroes (and Bobby Mimms) would go on to blow a first-half lead and finish the season empty handed in.

That second-half collapse hit him harder than his gran ever could. So hard he no longer possessed the heart to point out the blatant hypocrisy at play when, following the final whistle, the enraged arl hag powered up the stairs in a fit of uncommon (for her) elan, ripped her hallowed half Everton/half Red Shite Mersey-pride poster off the wall...and hurled it in the fucking bin. “Moustachioed pricks!,” she may as well have muttered.

If anyone had happened to have a camera handy back then, they could have surely captured the precise moment where caprice coalesced into malice. From that day forth, something began to ferment within her fragile frame. Pure unadulterated fume — given granny form.

He once considered his nan amongst the wisest women he had ever met, armed as she was with an entire lifetime of Machiavellian conniving and malevolent crone-like cackling behind her, but as she entered her final lap any remaining cunning and zest for football rapidly mutated into constant carping, moaning and zealotry. Everton were “effing crap”, every player was “a pansy” or “a ’ead the ball”, every manager “a divvy”, every official “under the arm”. She sent so many angry, spittle-flecked letters of complaint to the club, it’s a wonder she didn’t end her days like Grandma Death out of Donnie Darko, wandering diligently back and forth to the mailbox in a grotty dressing gown, anxiously awaiting a grovelling letter of apology from “that Kenwright divvy” that was destined never to arrive.

If ever her grandson attempted to proffer possible mitigating circumstances for any of the ‘amateurish’ antics currently going on at the club, her retaliatory words would always impact like a mighty right hook to the gut: “You’re going to end up like your bloody grandad, you”.

He certainly didn’t want that. He would rather slurp down the contents of a spilt liposuction sack with ‘Liza Minnelli’ scrawled on the label than suffer the cruel loss of memories lived to a sea of static and stupefaction. Nor did he want to end up like his own father, sipping morphine straight from the bottle to stifle pain brought on by prostate cancer that had already progressed to his core before he had even begun to suspect there may be something amiss.

The last time he saw his arl fella alive, he was sat up on his sick bed, all bruised skin and creaking bone, cursing the continual misfortune of EFC after the pair had sat and watched David Moyes’ men contrive to chuck away certain victory once more. Roused from a seemingly permanent, soporific state by the superhuman urge to point out to his son precisely how shite Everton's performance had been. Like soft lad would, somehow, have failed to notice for himself and needed the more senior blue to hammer the severity of the situation home.

Kind of fitting, as moans about Everton’s misfortunes had always had a monopoly on meetings between cynical kid and jaded old man. After a falling out, the first tentative step to getting back on good terms would generally be one asking the other “Did you watch the game?,” followed by the sort of super-accentuated, shared grimace of disgust Don Draper would have deemed absolutely perfect for that problematic 'Bag Of Shite' ad campaign.

Everton was the one constant in their relationship — the common ground that kept casual conversation from grinding to a complete halt. Not that they didn't get along or love one another, but there would have been a lingering undercurrent of awkwardness if football was absent as a crutch to fall back on. That was the entire reason he immersed himself so eagerly into all things Everton at such a young age in the first place: to please his previously aloof father, to understand what made him tick that little bit better, and to stop him thinking he was such an annoying little tit.

When he was a child, his old man was mostly a stranger to him, forced to find work abroad for years on end due to the mass unemployment that cut a cruel swath through stigmatised families on Merseyside during the 1980s. He remembered returning home from football practice one day, to find his dad stood, unexpectedly, in the kitchen and him kneeling down to speak to his kid sister. “Do you not know who I am?,” the errant head of the household enquired of his daughter, noticing the distinct look of confusion etched upon her face. “Yeah,” she replied with tears welling up in her eyes, “You're Thomas Magnum”.

Next morning, the minty eighties tash was gone for good and his sister suddenly twigged her chances of cruising about in a red Ferrari had swiftly followed suit. The elder sibling had little sympathy for the annoying short-arsed shadow who, most days, sauntered along after him post-school, pissing and moaning about football being ‘sooo stupid’, all while extolling the virtues of more serious pursuits — such as brushing the manes of miniature, brightly-painted, plastic ponies blessed with catchy names like ‘Butterscotch’ and ‘Bubblespunk’. As far as he was concerned, the forbidden colour of the rogueish P.I’s fanny magnet should really have tipped his sister to her fallacy far sooner than a freshly shaved flavour-saver.

Par for the course for his arl fella, after spending 14 years waiting for Everton to dust down the trophy cabinet, it seemed no sooner did his plane take off in desperate search of a pay packet, then so did the previously dreadful Kendall team. He missed the 84 FA Cup run, the entire 84/85 campaign, and came back for the climax of 85/86....and then he wondered why his son kept asking him when he was pissing off again as the start of the 86/87 season inched ever closer.

He was forced to celebrate Everton's most famous victory over Bayern Munich in South Africa with a bloke from Huyton he happened to bump into over there — a fellow blue whose idea of ‘partying’ was punching a poor monkey in the face after being pestered to have his picture taken with it for a pitiful fee. Understandably wary of being bounced up and down by a complete loon in a scratchy footie top with a brand of shit spam emblazoned across the front (and sadistically flicking its furry blue balls was surely the final straw), the mammalian model-for-hire had, quite reasonably, hissed a menacing warning towards the inebriated idiot who insisted upon calling him “Inchy” and “Hairy Adrian Heath”.

Without even having the decency to return the courtesy and completely forgetting that Clint fought alongside, not against, Clyde, the blue tag-along immediately went ballistic and began aiming blows at the “fast little bastard” until his fellow fan threw him forcefully aside. Suddenly surrounded by an angry mob, the pair legged it and split up, only for his father to be left looking over his shoulder all night in fear of being fingered later by a vexed Vervet with a fat lip.

He was always more hesitant about buddying up with fellow football fans after that. Following his return to the UK, his match-day ‘mob’ metamorphosed into a more tame triumvirate of himself, his young son, and his own mentally ailing father, Damian. Three generations of Evertonians, briefly getting to watch another slide from greatness but at least suffering together.

Of the three, he would have been considered the most optimistic. "Our time will come again,” he often used to say. Although, as he got older, he clearly believed it less and less. His wish list gradually withered. From wanting to witness Everton win the league again, it eventually scaled down to settling for seeing them lift a cup. Until, finally, as the cancer began to exert its chokehold on his chances of being around for any such future, he made the much more modest ask of staying alive long enough to see the blues beat those bastards at Anfield just one more time.

It never came to pass.

The last derby game he got to witness was a 0-0 draw at the cesspit, in which Everton were cruelly denied the win when a perfectly good Sylvain Distin goal was chalked off for reasons unknown to anybody other than the referee. It was a point Phil ‘pointy’ Neville would have proclaimed an “incredible” point, but for his father, it was one final pinch on the intravenous drip now fueling his nearly parched desire for all things Everton. Muttering away to himself after a post-match mouthful of morphine had muted his immediate physical pain, he tried in vain to make light of the situation — “At least I won’t ever have to watch another one” — before turning away to hide the fact he was on the verge of welling up.

“There’s always a bright side, son,” he used to say.

“Always”.

These memories of his forebears and many more came flooding back to the last surviving male of the family when, at the age of 40, he found out he was to be a father for the first time himself.

To say it was something of a surprise would be an understatement. He’d never wanted kids; indeed, he had made a conscious decision when he was much younger that he wasn’t cut out for parenthood due to a proliferation of pathetic character defects: an unshakable selfish streak, a fear of commitment, a love of financial freedom, along with a bad habit of drifting from place to place more than Dr. David Banner with a big 70s bag slung over his shoulder but minus the mournful piano music playing in his wake (though he did sometimes whistle it himself as he walked away. Not always. Occasionally he mixed it up and went with the theme from First Blood instead).

Yet, now that the seed had been planted and the relationship producing life was longstanding and strong, he became stirringly enthused at the prospect.

There was only one problem. An existential quandary. A Gordian knot he badly needed to get to grips with before his partner gave birth.

Could he really bring himself to consign his child to a barren existence as a true-blue Evertonian?

He didn’t think so. It would be what was expected, of course, but every fibre of his being initially screamed, “Fuck that”.

David Cooper, a prominent figure in the emerging ‘anti-psychiatry’ field of the 1970s, propogated that ingrained societal behaviours were steering western families towards inevitable insanity. It was his belief that being part of a family unit was akin to signing up for a suicide pact. Belonging to its ranks could only ever result in a descent into rage and alienation, as one came to realise it ruthlessly demanded a lifetime of ‘passive submission’ and ‘sacrificial offering’. The only way to avoid paying the price was to pull forcefully away from “one's whole family past”. Quite possibly a load of old queef, but when viewed through the prism of a long-suffering member of the extended Everton ‘family’, it seemed the boy may have been onto something after all.

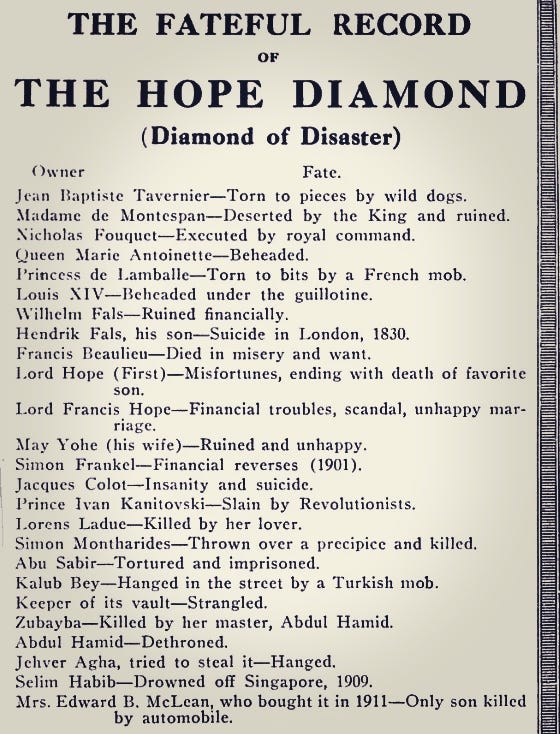

Perhaps Evertonianism was naught but a passed down curse? About half as deadly as the curse of the Hope Diamond maybe, yet much more cruel in its spirit-crushing methodology as it sadisticly cuts away at your hopes and dreams, slowly, over the span of several decades.

After all, hadn't everyone in his family who had been infected by ‘the blue blight’ ended up either barmy, bitter, or burrowed out by disappointment? He had already progressed too far down the same torturous path to ever turn back himself, but he saw no reason to try and entice an unborn child into taking up the baton and following along in well-trodden footsteps that would likely only lead to a massive sign saying, “That middling load of old bollocks you put up with for many years in the hope it might be a precursor to better things? That's your lot, lad”.

Would a child's life not be better minus the inevitable misery and disappointments, or do the few fleeting moments of success really make it all worthwhile?

What would his predecessors think if Everton were given the push by his progeny? Would they view it as a betrayal? Taking a slash on the family sigil? A crime akin to the one committed by whichever cock-womble came up with that weird cartoon badge a couple of years back?

Perhaps it would be like lopping off a gangrenous limb, saving future generations from the same fate?

What would they be missing out on?

What could they replace it with?

He half hoped he had scored a spermy brace so as to carry out a social experiment. Raise one a bluenose while excluding the other from Evertonianism entirely. See who has a happier, more fulfilling, less angst-ridden life. Maybe he could let the other one be a glory boy and support a more successful side, he mused. He could never countenance ‘Subject 2’ supporting the RS, though. That would make him no better than the cold-hearted scientist in Twins who gave all the good genetic soup to Arnold Schwarzenegger and saddled Danny Devito with all the leftover slop.

While he was pondering all this, his poor partner was suffering through actual real-world problems, retching and puking nearly non-stop. Puking like a Team America puppet. Torrents of the stuff. All day, every day. Until, in the end, she couldn’t even drag herself out of bed anymore or stand without support.

Slopping out sick bucket after sick bucket, he found himself thinking it was as if Father Karras from The Exorcist had come to stay and was trying his damnedest to cast the gestating Everton curse out every day. From the crack of dawn to the eventual drawing of curtains, the sight, smell, and sound of copious amounts of seemingly demonic vomit continued to serve as the maternal mise en scène.

Certain doctors dismissed any and all concerns, declaring it to be just 'normal’ sickness that ‘everyone goes through', which would spontaneously stop as if by magic once she made it to 16 weeks. Others palmed his partner off with patronising suggestions straight from the pages of ‘Woman’s Weekly’ like ‘go for a walk’, ‘eat biscuits’, ‘swallow some ginger’, ‘sip tea’, or ‘smile, Prince William’s wife went through the same thing’.

Eventually she was diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum (HG). Affecting around 3% of pregnancies, it can rapidly prove debilitating for sufferers due to the continual struggle to keep any food or fluids down at all. Dehydration, severe weight loss, countless sessions hooked up to an intravenous drip, steroid shots, heparin injections in the abdomen and the sporting of appallingly non-sexy stockings to prevent DVT and a pulmonary embolism soon ensued and persisted throughout the entire pregnancy.

At 27 weeks, their son was born.

It had already been decided that he would be named Damian, after his great-grandfather.

His mother had been to see the baby before him and came back breaking her heart.

The boy weighed about the same as two tins of beans. So many wires and tubes meshing with flesh to seemingly form a fragile bio-mechanical bundle.

Eyes fused shut. Ears that fine and malleable they were like an impression of the real thing left on tracing paper.

His skin was a wafer-like shield, ever shifting in colour. At first, so thin it appeared near translucent, the blood beneath visible to the world beyond. It worked it's way up to albino white, before a worsening gastrointestinal problem turned it's weak pallor grey.

Doctors told them not to get their hopes up, while nurses mentioned they had witnessed numerous miracles.

Almost every day there seemed to be a fresh threat for the child to overcome. Every positive sign was swiftly followed by a further impediment to his survival.

Moments of skin-to-skin — or 'kangaroo' — contact were said to be crucial, yet it was made clear they could not risk holding their son for more than a couple of minutes at a time. They felt like touch thieves, snatching brief samples of a simple pleasure every parent should be able to take for granted. Cherishing the chance to cradle their child, but ever fearful of getting carried away in the moment and clinging on for a fraction too long.

Time moved like a tectonic plate. Slow, dragging days, sinking one into another, each indistinguishable from the next. The same tests and checks and observations. No change. No change. Fuck off, no change. The feeling of being in free fall and giving the finger to inertial frame.

Futile efforts to find mooring meant fumbling for meaning in the meaningless. The gift of a baby kit (that he couldn’t yet wear but clung on to for a bit) from a family friend, followed by a fairly good day for the boy, meant that the garment became the little fellas ‘lucky blue shirt’ in a flash.

The power of positive thinking was preached relentlessly, and it was recommended that they mentally picture and then focus upon a prospective family activity—a place, an event—that they could attend together in the not-too-far-off future, parent and child, when their current problems were merely a thing of the past. For all his early-pregnancy protestations to the contrary, the first place that came to mind was Goodison Park.

Going the game. Father and son. For the first time.

He realised then that it was pointless trying to evade it. That’s the way it had always been with his family. The way it always would be.

He set to work schooling him straightaway. The analgesic benefits of persistently hearing a parent's voice had been stressed previously, so he sat and passed on all the tales of Everton his grandfather had regaled him with in his youth. The pre-war title-winning team, the post-war relegation, the holy trinity, the waking of Kendall’s slumbering giants, he relayed them all and continued on through the dogs of war, David Moyes, and the day amateur breakdancing champion Richard Wright did the reverse caterpillar over a ‘Keep Off The Wet Grass’ sign in the box during a warm-up.

He muted the volume on dodgy match day streams and stood, self-consciously, in the centre of the room, giving his son a running commentary, embellishing events unfolding throughout the game. Going into far too much detail and failing to dial down his ever-growing frustration at the depressing goings-on at Goodison Park, the captive audience that was his poor child probably dreaded falling asleep in case entering the dreamscape brought him face-to-face with one of the nightmarish footballing oddities his father had deemed fit to warn him about, such as the legendary ‘Carthorse Keane’ creature (Daddy’s description: Basically, a McCains Potato Smiley shoved on top of the body of the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, who spent 90 minutes each week like he’d misread the words from the Necronomicon and was now navigating the game with a group of mini-Michael Keane’s sabotaging his every move — stabbing him in the foot, jabbing a fork in his arse, holding his eyelids shut, tripping him up, and dancing round his feet every time the ball came near).

Eventually, there came continued improvement. Damian grew stronger, gained weight, was no longer dependent on a feeding tube. A period of ‘rooming in’ went well and provided reassurance that their baby was finally, thankfully, ready to come home.

They thought the change of environment might be daunting for him, but he settled in at once. Damian was a joy, their perfect little boy. Everything was back on track and only going to get better from thereon out.

Then, one day, Damian didn’t feed as often as he normally did. The next day, not at all. By the time they got to the hospital their son was struggling for breath.

He had left home in his ‘lucky’ blue shirt.

At first they were told it was ‘probably a cold’, then bronchiolitis — a chest infection causing congestion and blockages in his lungs. Then their boys lips turned as blue as that ‘lucky’ shirt and his body suddenly went limp like the life was being leeched out of him.

With a final flicker of blue, Damian closed his eyes.

There are an endless number of things he never got to see his son do, but he saw him smile while wearing an Everton shirt and watched him fight like hell in one too.

He had initially bristled at raising his son an Evertonian, but now he feels him sat right beside him at every single game. When he shuts his eyes, he swears he can see him, not as he was, but as he would have been: a little boy, face full of wonder, fully focused on the action unfolding out on the pitch, proudly wearing blue.

He momentarily recognises him in the partisan face of every small child roaring alongside a parent, and, while such a sight may produce a sharp pang of envy, merely being in close proximity to fellow supporters and their families, knowing they are forging the foundation of a further unifying bond that will stubbornly persist throughout good times and bad, serenity and strife, success and shite, simultaneously comforts as much as it cuts.

He used to believe it to be nothing more than a corny merchandise-shifting soundbite, but now he knows it to be true. 'Evertonians are born, not manufactured', and, if you were to ask him, he would say he feels truly blessed to have been able to experience it for himself, fresh seeds burgeoning within his boy, even if only for the briefest moment in time.

Damian was an Evertonian, the first AND last of a thick and thin blue line.

Incredibly moving.